From the beginning, the most important feature of Binary Ninja has been our API. The goal is simple: your plugins should be capable of producing the same high-quality decompilation as our official architectures. In this three-part series, we will implement a complete architecture and platform using some lesser-known features in Binary Ninja. From disassembly and lifting, to calling conventions, Type Libraries, and function signatures, we will explore the many steps involved in getting and refining decompilation results. The series is intended to be used both as a roadmap for how to build your own architecture plugin and as ideas for how to improve an existing one you might already have.

Note: Third-party plugins are a paid feature of Binary Ninja, so you will need a license to the Personal edition or higher to write an architecture of your own. Apart from that, plugins are compatible with all paid editions and even with collaboration support on the Enterprise edition.

Contents

This is Part 1 of a three-part series. Here is the full list of contents:

Target

The target of these new tools is the custom VM-based architecture Quark, available as a compilation backend in Binary Ninja’s Shellcode Compiler (SCC). It comes complete with an interpreter, a standard library, and a full compiler suite for creating test programs. Having a toolchain available to produce objects for the target was quite helpful during implementation, as assumptions we make about how the target works can be tested relatively easily, and getting sample binaries was not an issue.

The architecture is a 32-bit register-based VM with 68 instructions, including a full set of load/store, arithmetic, and control flow operations. All instructions are packed into 4 bytes, and execution is a simple switch-based loop with each instruction acting independently. Conditional branches are handled by every instruction having the option to be conditionally executed, which is only used for jumps in compiled executables but could theoretically apply to any instruction. It has 32 4-byte registers, including a stack pointer, addressable instruction pointer, a link register, and four flags that can be used with any operation. A standard library of functions is included, with a decent amount of the C standard implemented. Library functions are always statically linked (no dynamic linking), and it uses system calls based on the operating system executing the VM. Overall, while the architecture is pretty simple, the full compiler and standard library make it good for demonstrating Binary Ninja’s extensive set of features available for you to use.

Setup

The first step in creating a plugin for a custom architecture is defining an Architecture subclass. We need to fill out a bunch of metadata about the architecture, most of which will not be used until much later.

class QuarkArch(Architecture):

name = "Quark"

endianness = Endianness.LittleEndian

address_size = 4

default_int_size = 4

instr_alignment = 1

max_instr_length = 4

regs = {

'sp': RegisterInfo('sp', 4),

# ...

'lr': RegisterInfo('lr', 4),

# ...

# Note: IP register can be defined here, but we will not use it (explained later)

}

stack_pointer = 'sp'

link_reg = 'lr'

QuarkArch.register()

SCC conveniently gives us the option to produce object files as ELFs, so we will not need to write a BinaryView file format parser for this project. We can register our new architecture with the existing ELF loader, and Binary Ninja will automatically pick up the custom machine type and start using our new architecture without needing to click anything in the UI:

# Later, we will see this is not a complete solution

# But for now, we can register with the appropriate machine type (4242),

# and then loading a Quark ELF will automatically create a start function

# at the entry point using the Quark architecture.

BinaryViewType['ELF'].register_arch(4242, Endianness.LittleEndian, Architecture['Quark'])

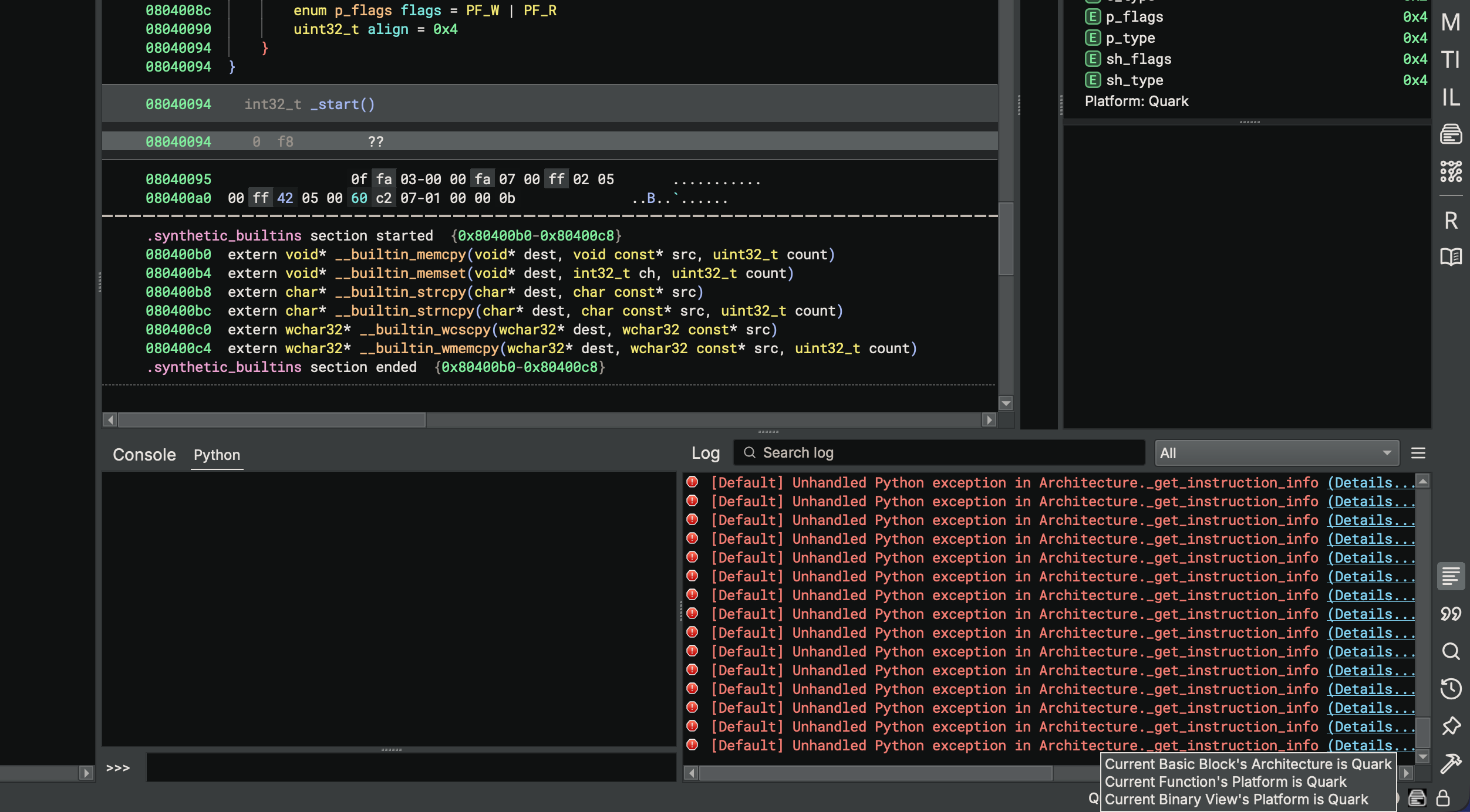

No decoding yet, but we now have a Quark function created at the entry point.

No decoding yet, but we now have a Quark function created at the entry point.

It might not look like much yet, but thanks to Binary Ninja’s existing ELF parser, we get to skip a significant amount of work parsing binary files, and we can skip directly to decoding bytes.

Disassembly

Decoding

Before we can disassemble the instructions, we need to decode them. In the case of Quark, instructions are always 4 bytes, in a single stream, and there are no segments to differentiate between code and data (a Von Neumann architecture). Binary Ninja will feed instructions to our subclass’s implementations of get_instruction_info and get_instruction_text to determine instruction size and text. We can make a trivial implementation of both and see instructions start lining up:

def get_instruction_info(self, data: bytes, addr: int) -> Optional[InstructionInfo]:

result = InstructionInfo()

result.length = 4

return result

def get_instruction_text(self, data: bytes, addr: int) -> Optional[Tuple[List['function.InstructionTextToken'], int]]:

tokens = []

# We will fill out tokens in the next section

return tokens, 4

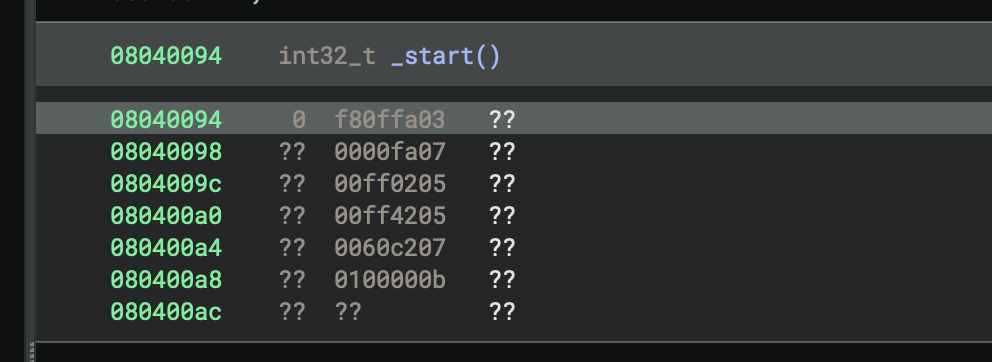

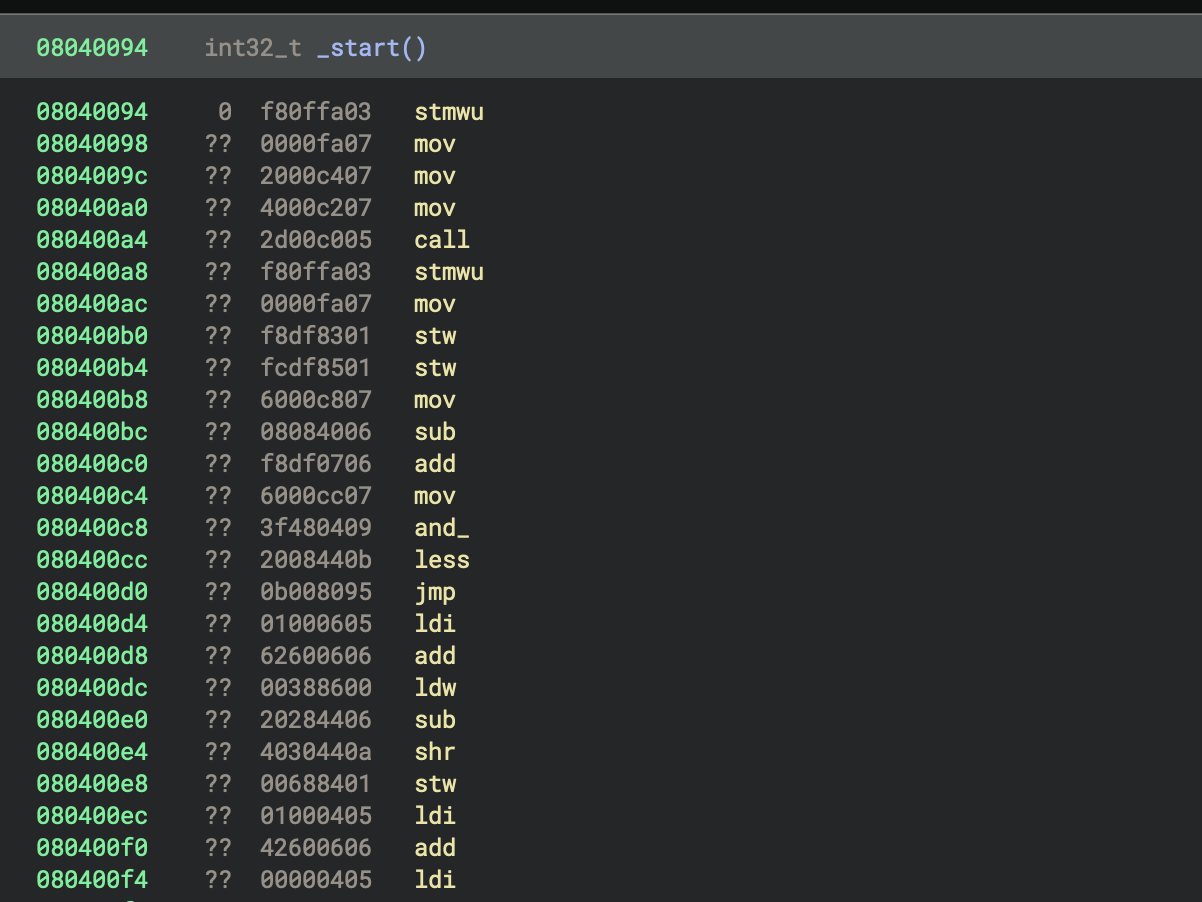

Our instructions, ready to be decoded

Our instructions, ready to be decoded

Quark packs a number of different fields into each 4-byte instruction using bit-shifts and masks to read out opcode, operands, and conditions. We can look at the interpreter source to see precisely how this is done:

uint32_t instr = *(uint32_t*)(r[IP]);

uint32_t cond = instr >> 28;

uint32_t op = (instr >> 22) & 0x3f;

uint32_t a = (instr >> 17) & 31;

uint32_t b = (instr >> 12) & 31;

uint32_t c = (instr >> 5) & 31;

uint32_t d = instr & 31;

// ...

We can model this in Python with a bit of structure unpacking and integer math:

class QuarkInstruction:

def __init__(self, instr: int):

self.instr = instr

@property

def cond(self):

return self.instr >> 28

@property

def op(self):

return (self.instr >> 22) & 0x3f

@property

def a(self):

return (self.instr >> 17) & 31

@property

def b(self):

return (self.instr >> 12) & 31

@property

def c(self):

return (self.instr >> 5) & 31

@property

def d(self):

return self.instr & 31

# ... various other properties like larger immediates skipped for brevity

Then, as a convenience aid, we can have the disassembly text show us the value of these fields:

class QuarkArch(Architecture):

# ...

def get_instruction_text(self, data: bytes, addr: int) -> Optional[Tuple[List['function.InstructionTextToken'], int]]:

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

tokens = []

tokens.extend([

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, 'cond: '),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, f'{info.cond}'),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, ' op: '),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, f'{info.op}'),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, ' a: '),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, f'{info.a}'),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, ' b: '),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, f'{info.b}'),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, ' c: '),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, f'{info.c}'),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, ' d: '),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, f'{info.d}'),

])

return tokens, 4

Disassembling the instructions into their various integer fields

Disassembling the instructions into their various integer fields

Printing out the components like this is helpful when determining whether we handled endianness correctly. If it was not right, we would see invalid/undefined opcodes or condition values where we wouldn’t expect them. Now that we have the component parts of our instructions decoded, we can proceed to disassembling, where we turn those components into text.

Disassembly Text

Being a custom VM, Quark doesn’t have a specification for how the disassembly text is formatted. Even so, we can use the opcode mnemonics found in the interpreter as a starting point. We can put all of them into an enumeration for easy reference:

class QuarkOpcode(enum.IntEnum):

ldb = 0x0

ldh = 0x1

# ...

# These are grouped into another enum, based on `b`

integer_group = 0x1f

# These are another group, based on `b & 7`

cmp = 0x2d

icmp = 0x2e

class QuarkIntegerOpcode(enum.IntEnum):

mov = 0x0

xchg = 0x1

# ...

class QuarkCompareOpcode(enum.IntEnum):

lt = 0

le = 1

# ...

Then, we can make the disassembly text show us the opcode mnemonics:

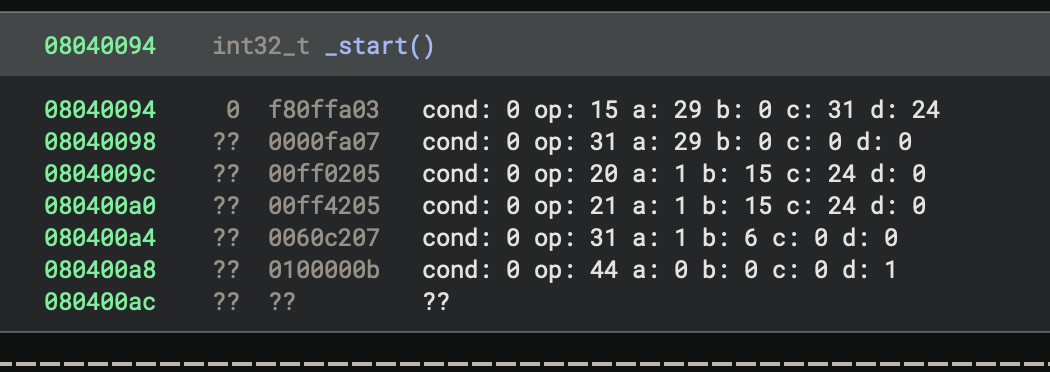

def get_instruction_text(self, data: bytes, addr: int) -> Optional[Tuple[List['function.InstructionTextToken'], int]]:

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

op = QuarkOpcode(info.op)

tokens = []

# Python 3.10 match statements

match op:

# Integer ops and compare ops split out into their own groups

case QuarkOpcode.integer_group:

int_op = QuarkIntegerOpcode(info.b)

match int_op:

case _:

tokens.extend([InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.InstructionToken, int_op.name)])

case QuarkOpcode.cmp | QuarkOpcode.icmp:

cmp_op = QuarkCompareOpcode(info.b & 7)

match cmp_op:

case _:

tokens.extend([InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.InstructionToken, cmp_op.name)])

case _:

# Just render mnemonic for now

tokens.extend([InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.InstructionToken, op.name)])

return tokens, 4

It’s doing something and then doing a syscall

It’s doing something and then doing a syscall

We can see the previous sample looks reasonable, but is not very long. Let’s load a larger binary to be more confident that the opcodes are being decoded correctly. The patterns of the instructions seem sensible, despite not having any operand printing or function boundaries yet:

A bunch of moves followed by a call seems very likely correct

A bunch of moves followed by a call seems very likely correct

From this point, the rest of disassembly involves choosing a format for rendering the operands and implementing them one by one. This is largely a straightforward process, as mistakes are pretty easy to spot given the pure text output. Here are a couple notes from the process:

- Calls and jumps in Quark are based on

ip-relative addresses, calculated afteriphas incremented, so we need to useoffset + addr + 4to calculate their destination. - Operations that refer to the

ipregister need special printing, as theipregister is not included in the Architecture’sregslist. The reasoning behind this special handling ofipis addressed later, but for now we can make a helper function for getting register names that handles this special case. - More complicated addressing modes are consistent across instructions, so we can split them out into a helper function that returns a list of tokens.

- Quark represents constant subtractions as additions with two’s complement constants. We chose to resolve this during disassembly and represent additions with values over 0x80000000 as subtractions.

- Using PyCharm and

matchstatements, we can tell we are no longer missing any opcodes because thecase _:statement at the end was marked as unreachable when every enum variant was implemented.

We will use the following pattern for disassembly:

def get_instruction_text(self, data: bytes, addr: int) -> Optional[Tuple[List['function.InstructionTextToken'], int]]:

# ...

tokens = []

if info.cond & 8:

if info.cond & 1:

tokens.extend([

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, "if"),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, " "),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.RegisterToken, f"cc{(info.cond >> 1) & 3}"),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, " "),

])

else:

# ...

match op:

case QuarkOpcode.ldb | QuarkOpcode.ldh | QuarkOpcode.ldw | QuarkOpcode.ldbu | QuarkOpcode.ldhu | QuarkOpcode.ldwu | QuarkOpcode.ldsxb | QuarkOpcode.ldsxh | QuarkOpcode.ldsxbu | QuarkOpcode.ldsxhu:

tokens.extend([

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.InstructionToken, op.name),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, " "),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.RegisterToken, reg_name(info.a)),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.OperandSeparatorToken, ", "),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.BraceToken, "["),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.RegisterToken, reg_name(info.b)),

*cval_tokens(plus=True, zero=False, signed=True),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.BraceToken, "]"),

])

case QuarkOpcode.jmp | QuarkOpcode.call:

dest = addr + 4 + i32(info.imm22 << 2)

tokens.extend([

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.InstructionToken, op.name),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.TextToken, " "),

InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.PossibleAddressToken, f"{dest:#x}", value=dest),

])

# ...

case _:

tokens.extend([InstructionTextToken(InstructionTextTokenType.InstructionToken, "??")])

return tokens, 4

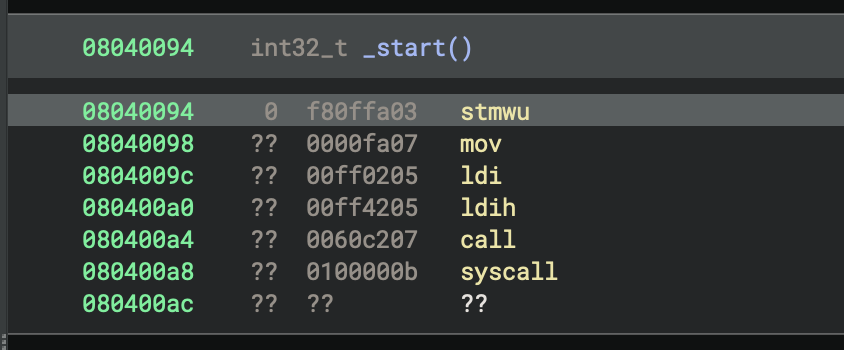

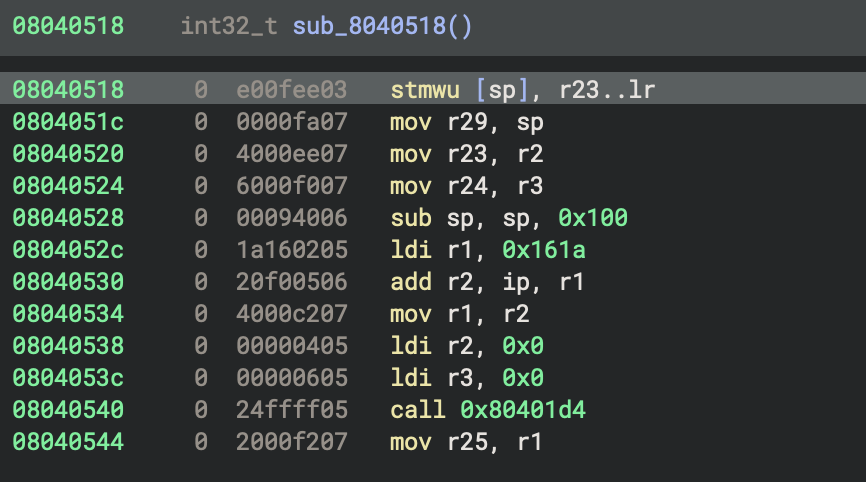

After implementing disassembly for every opcode, we start to get some nice output:

Looking like a real disassembler now

Looking like a real disassembler now

In total, implementing the disassembly for Quark took a few hours. The broad range of support provided by Binary Ninja made this process relatively easy to debug, and most of the time was spent trying to construct a disassembly format that looked nice.

Control Flow

We now have instructions presented nicely, but there is no structure to our disassembly. We need to tell Binary Ninja where the control flow is, so it can split basic blocks and search for functions. This is done by adding details to get_instruction_info that report which instructions are branches. While we don’t need to know the target of every branch, the more information we can fill in during this stage, the better our basic block analysis will be. There are a couple of things to consider:

- Quark’s calls and jumps are

ip-relative, so we need to calculate those here too, being sure to account foripmoving before the address is calculated. - For conditional jumps, we should make sure to branch to the next instruction for the false case.

- Operations moving into

ipcount as jumps. We could special caseip = lrbut don’t need to. - System calls don’t have real destinations but can be marked as branches anyway.

For the implementation of this, we can use a similar pattern to the disassembly:

def get_instruction_info(self, data: bytes, addr: int) -> Optional[InstructionInfo]:

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

op = QuarkOpcode(info.op)

result = InstructionInfo()

result.length = 4

match op:

case QuarkOpcode.jmp:

if info.cond & 8:

if info.cond & 1: # Jump if condition is met

result.add_branch(BranchType.TrueBranch, addr + 4 + i32(info.imm22 << 2))

result.add_branch(BranchType.FalseBranch, addr + 4)

else: # Jump if condition is NOT met

result.add_branch(BranchType.TrueBranch, addr + 4)

result.add_branch(BranchType.FalseBranch, addr + 4 + i32(info.imm22 << 2))

else: # Unconditional jump

result.add_branch(BranchType.UnconditionalBranch, addr + 4 + i32(info.imm22 << 2))

case QuarkOpcode.call: # Call relative

result.add_branch(BranchType.CallDestination, addr + 4 + i32(info.imm22 << 2))

case QuarkOpcode.syscall: # System calls can be annotated, too

result.add_branch(BranchType.SystemCall)

case QuarkOpcode.integer_group:

int_op = QuarkIntegerOpcode(info.b)

match int_op:

case QuarkIntegerOpcode.mov: # E.g. mov ip, lr

if info.a == self.ip_reg_index: # ip is not a real register in our plugin

result.add_branch(BranchType.IndirectBranch)

case QuarkIntegerOpcode.call: # Indirect call

result.add_branch(BranchType.CallDestination)

return result

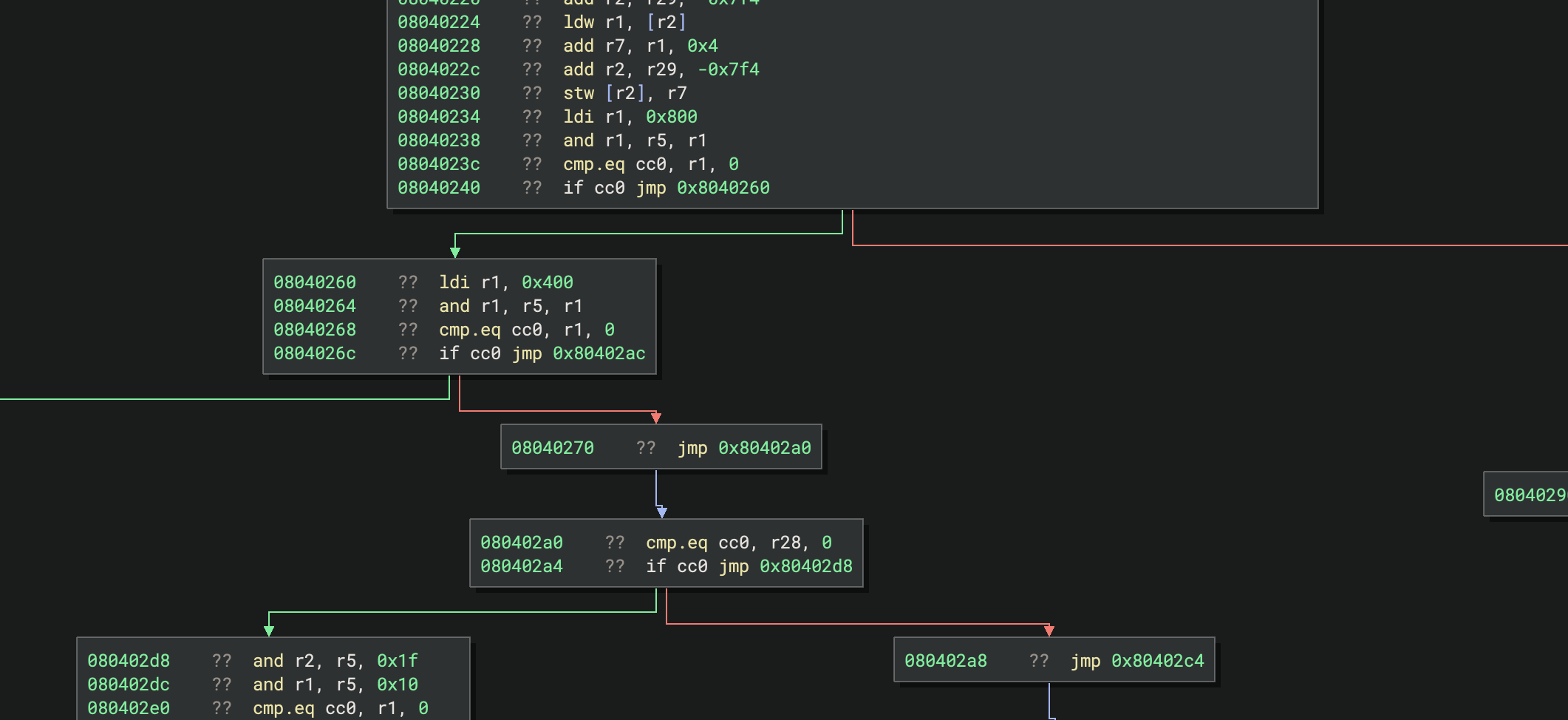

Now branches split control flow properly

Now branches split control flow properly

For a small amount of work, we get large improvements in readability! Instructions are now split into basic blocks, and Graph View lets us pan around the code and see control flow structures. This is likely good enough for implementing a disassembler for most people. That said, there are still a few other optional improvements we can add.

Addendum

Instructions in Quark are based entirely on details contained within the 4-byte instruction. Other architectures may make use of data contained elsewhere in the binary or have instructions based on state set by previous instructions. Historically, it wasn’t possible to handle those cases as Architecture plugins would only get one instruction at a time. However, recent additions to the Architecture API let you override AnalyzeBasicBlocks, the part of analysis responsible for disassembling an entire function. This allows you to pass context data to get_instruction_text_with_context instead of using the context-free get_instruction_text. More detail for these new features will be covered in a future post, but for Quark we only need to handle one instruction at a time with no need for context, so we will not be covering that here.

Additionally, Quark instructions’ dataflow is all specified within each instruction. Some architectures don’t follow this pattern and allow patterns like loops with branches specified by previous instructions that are not observed until later. Delay slots can also be tricky to implement, and historically have been done via lifting each instruction with multiple instructions’ worth of data and reordering them if necessary, though the recent Architecture changes should make this unnecessary as well. Either way, those are also not going to be covered here as Quark’s execution flow is rather trivial.

Other topics not covered here, but you may need to support in your architecture:

- Register Stacks: Certain architectures (like x86’s x87 FPU) have a “stack” of registers which can have values pushed and popped (but are still backed by a fixed count of registers). These are moderately well-supported by Binary Ninja, but so infrequently used that their documentation is sparse. Look at the x86 architecture plugin as a reference if you need these.

- System Registers: Registers set by the system, they are assumed to be volatile. Reads from them and writes to them will never be dead code eliminated.

- Global Registers: Certain platforms have registers that are referenced by functions but set by the operating system, and they should not be considered as parameters to functions. These can also be defined by a Platform, check back for Part 3 for more information on those.

Patching

Binary Ninja has built-in support for easy patching of code, which is powered by a few callbacks on Architectures. This patching is great to have when reversing code, as it offers a brute force way to clean up messy functions or remove checks that could prevent you from executing certain branches of the binary.

Here are the available patch operations:

- Convert to NOP: The most commonly used, this replaces the selected sequence of bytes with

nopinstructions. - Always/Never/Invert Branch: Available on conditional branch instructions, these change the behavior of the branch.

- Skip and Return: Available on call instructions, this lets you replace the call’s result with a constant.

Implementing these is simple: First, inform Binary Ninja that you support each patch operation:

# Convert to NOP does not have a callback. It will be available if the

# selection does not have the "never branch" patch available.

def is_never_branch_patch_available(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> bool:

# Make sure the data is a conditional branch

if len(data) != 4:

return False

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

return info.cond != 0

def is_always_branch_patch_available(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> bool:

# ... same as above

def is_invert_branch_patch_available(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> bool:

# ... same as above

def is_skip_and_return_zero_patch_available(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> bool:

# Make sure the data is a call

if len(data) != 4:

return False

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

return info.op == QuarkOpcode.call or (info.op == QuarkOpcode.integer_group and info.b == QuarkIntegerOpcode.call)

def is_skip_and_return_value_patch_available(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> bool:

# ... same as above

Then, the callbacks for applying the patches are given the current bytes at the address to patch and should return some bytes to replace them. In support of this, we first add some setters to the various fields on the instruction structure:

class QuarkInstruction:

# ...

@cond.setter

def cond(self, cond):

self.instr = (self.instr & 0b0000_1111_1111_1111_1111_1111_1111_1111) | ((cond & 0xf) << 28)

# ...

Then, patching instructions just involves mutating the instructions as provided:

def convert_to_nop(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> Optional[bytes]:

# No need to be fancy here, just repeat a sequence that does nothing

# Could also set QuarkInstruction.cond = 1

return b'\x00\x00\xc0\x17' * (len(data) // 4)

# Never branch uses convert_to_nop

def always_branch(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> Optional[bytes]:

if len(data) != 4:

return None

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

info.cond = 0 # Clear conditional execution flags

return info.instr.to_bytes(4, "little")

def invert_branch(self, data: bytes, addr: int = 0) -> Optional[bytes]:

if len(data) != 4:

return None

info = QuarkInstruction(int.from_bytes(data, 'little'))

info.cond = info.cond ^ 1 # Toggle if the instruction is skipped

return info.instr.to_bytes(4, "little")

# Skip and return zero uses skip_and_return_value(0)

def skip_and_return_value(self, data: bytes, addr: int, value: int) -> Optional[bytes]:

info = QuarkInstruction(0)

info.op = QuarkOpcode.ldi

info.a = 1 # return reg is normally r1

info.imm17 = value

return info.instr.to_bytes(4, "little")

Adding these is a nice quality-of-life improvement to reversing code with your architecture, but they are not necessary and can be skipped if they are too cumbersome to implement. Here, we’ve implemented them by modifying the instructions directly, but you can also implement them by assembling new instructions if you have an available assembler.

Assembling

Integrating a full assembler into your architecture plugin is a nice feature for testing decompilation. Being able to assemble custom instructions lets you hand-construct functions to test obscure instructions that may not be possible to find in compiled binaries. While implementing an assembler is outside the scope of this article, we did write one for Quark, so you can see here how we integrated it.

The first step to adding an assembler is informing Binary Ninja that your architecture has one:

class QuarkArch(Architecture):

# ...

# Python's syntax to override a parent class's property

@Architecture.can_assemble.getter

def can_assemble(self) -> bool:

return True

Then, the assemble method is straight-forward. The only context that Binary Ninja gives your assembler is the text of the assembly and the address of the first instruction. You will need to calculate later instructions’ addresses in your assembler and should use these addresses for emitting relative offsets/jumps. Also of note: if the assembled code is shorter than the original code, Binary Ninja will fill the remaining space with nop instructions as emitted by the convert_to_nop patch function.

With all that considered, the boilerplate for assembling instructions is pretty minimal:

def assemble(self, code: str, addr: int = 0) -> bytes:

# Turn `code` into bytes

try:

result = ...

except:

# Raise a value error if there is a syntax error in the assembly

raise ValueError("could not assemble: <...>")

return result

Now, Binary Ninja will let us edit lines and create entire blocks of code from assembly text:

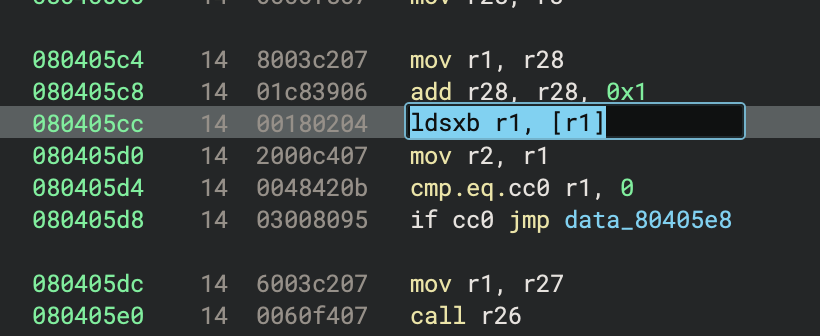

Pressing E on a line will let you modify the disassembly

Pressing E on a line will let you modify the disassembly

Conclusion

Writing a disassembler is the first step towards getting rich analysis for a new architecture. Many analysis tools would get to this state and be content–but with Binary Ninja we can go further! Implementing a lifter will allow Binary Ninja to decompile this architecture all the way to Pseudo-C, enabling use of its powerful analysis tools along the way. Check out Part 2, where we implement a lifter and start to see actual decompilation.

In the meantime, we’d love to hear if you have any questions or feedback.